personal reflections on books. review is too grand a term for this collection of thoughts on whatever i am reading currently.

Friday, June 25, 2010

Book journaling 1

Full Moon by P.G. Wodehouse

Blandings Castle will routinely have young people banished to the rural countryside for being in love with the wrong sort, wily attempts by these 'wrong sort' of lovers to get back together with their beloveds and a misadventure with the Empress, the pig-in-residence, not to mention 'hordes of wild aunts' - all profiled for the discerning reader by the finest craftsman of sentences known to mankind. Full Moon has all these and more.

The Aye Aye and I by Gerald Durrell

If you've read earlier books by Gerald Durrell, the most striking thing about this novel is the maturing of the 'green movement'. His first books were full of lonely struggles written about with excellent good humour and a great sense of timing. This one constantly refers to organisations and institutions that now fight the good fight to keep planet earth inhabitable for all its inhabitants. Possibly for that reason, the humour does not sparkle as much. The writer himself is aging and writes about the difficulties of old age with his trademark humour. But the thrill of adventure that animated earlier books, where many things hung on a thread, and that gave a sharper edge to the jokes, is missing.

The Mammoth Book of Best New Manga ed. by Ilya

If you're looking for an introduction to manga (like I was), this is not a good book to begin with. If you're looking for an extremely diverse collection of short stories, told in all sorts of innovative visual styles, this one is for you. This is a collection of artists across the world, using manga to tell various kinds of stories. I loved the diversity of it. Only the first story seemed to give me a feel for the the shape of the form. Then I lost myself in multiple stories. The switches between the styles of various artists/cartoonists/writers is extremely disconcerting. This is a true roller-coaster ride - the stories can turn your stomach, leave you in the middle of free fall and set you back on the ground wanting to do it again:)

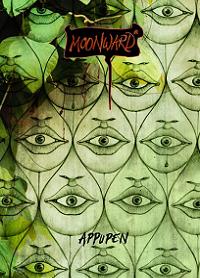

Moonward by Appupen

Moonward is a dark, satirical, serious-funny story. An overwhelmingly visual tale. Nothing in this book is fiction. Nothing is real. A dystopia, so clearly shaped by the world we inhabit, that makes you wonder why we don't ask the questions this book asks. This book is a contained scream of rage. Which is also funny. The tale moves like a nightmare between what is real, could be real and might soon be real, between horror, fear and the desperate need for respite. It's savagely funny - holding up the skeletons of our lives for laughs, showing us the graphic realities of our times in gray, black and white. Highly recommended.

The Bartimaeus Trilogy

The first of a trilogy - but the other two books are sadly not available on Book and borrow:( The book sounds too much like Harry Potter in the earlier half but the similarities gradually dissolve. Nathaniel is a much more finely developed human-sounding character than Harry. For one, he literally shapes his own destiny. An act of vengeful spite turns into a nightmare of angry magic, death, conspiracies against the government and the development of a tense relationship between Nataniel and, the djinn he invokes, Bartimaeus.

Thursday, May 13, 2010

Johnny and the Bomb by Terry Pratchett

Travelling in time has become a well-worn narrative. There are certain conventions in time travel stories now: If you go back and change something in the past, the present you return to will be either unrecognisable or changed in subtle ways. You require a machine to do time travel in. Johnny and the Bomb shines because of its play with these conventions. Gunk inside a garbage bag in a shopping trolley can transport you in time. Also, if you can run in space, you can also run through time. Who knew? It doesn't overturn all conventions, it plays with some, it adheres to others.

It is imbued with Pratchett's deep respect for human life. A death in a Pratchett novel is not an easy occurrence. His young protagonists are tested to the very limits of their ingenuity in their quest in this book to save twenty lives in a WWII bombing.

This book is a delight because of Pratchett's style of storytelling, always ethical, always critical and always funny.

Sunday, February 7, 2010

Soul Music by Terry Pratchett

Terry Pratchett has a brutal sense of humour that rips into religion, government, pop culture, academia and just about anything that's lying around with a button that says 'Do NOT touch'. Satire, fiction, sci-fi, fantasy, humour - attempting to classify the work of the most brilliant writer I know is not a task for the faint-hearted.

This particular book stars Death, his grand daughter and a boy that seems elvish, a dwarf, a troll and some very angry Guilds. Oh and some wizards who have uncontrollable urges to wear black leather and plaster the walls of their Unseen University rooms with posters.

Tuesday, July 1, 2008

Ursula K. Le Guin, 2004, Gifts, 2006, Voices

"What's to gain by silence?", Cannoc in Gifts

Ursula Le Guin is a thorny writer. Her words and sentences cling to the intellect like burrs, asking questions in an annoying, low, raspy voice. Two thorn bushes that I fought my way through recently are Gifts and Voices, the first two installments of the Annals of the Western Shore.

Gifts is a quieter, more contained tale, only venturing outside its chosen locale in the stories within the story. The outside world, literally and through story, pulses in the streets of Ansul in Voices.

In Gifts, the hills from which the Uplanders scrape out a livelihood, close the reader in with a cold tale, rain lashed with occasional patches of sunlight. It is a story of magic and coming of age in the mountainous Uplands. Families with gifts to undo, heal, call the animals and lay curses maintain a fragile peace, trying not to incite centuries-long feuds between clans. Here, when women within the clan with the gift to destroy grow scarce, a man finds a bride from the Lowlands and a son that is born to them.

Only, in the lineage of the gift of undoing, he is a boy with the gift of making song and story, holding an audience in rapt silence with the words he learnt from his mother. This is the story of a boy learning to be a man, confronting a lie that held the borders of their domains safe for many a year and learning to grieve and be strong. The gifts weave their way through the story almost like myth. Except for the death of the dog, the snake and the laying waste of a hillside, the reader might well agree with the outsider Emmnon that the belief in the gifts have kept the families separate is superstition. The gift of making is, however, true and brings healing to grief.

The boy breaks away from traditions in many ways. He decides to leave for the Lowlands with the childhood sweetheart who has stayed by his side through testing times in pursuit of the dream of a better life away from the hard, vengeful living in the hills. The Uplander who learnt to read and sing finds another purpose, another role in Voices.

Voices is set in the city of Ansul, a city that ruled itself with a semblance of democracy - the city that becomes the locus for the struggle to remain literate. The Alds, modelled on the Arabs, enslaved the proud city, banning reading and writing among a people that prided itself on its knowledge and its heritage of folklore about heroes. The Alds are clearly a reflection of a mono-theist, desert-dwelling, misogynistic stereotype. They are fair, though, while the Ansul women are described as brown and round-cheeked. The Ansul dwellers are pantheist, peace-loving and originally in possession of a university that was destroyed by the invading Alds. A travelling story teller, whom we have already met in Gifts, and his wife with a lion that she calls with her gift for calling animals shape the story's crucial twists and turns.

A 'half-breed' born after the rape of an Ansul woman by an Ald soldier is the unwilling heroine. The need to sustain learning and keep alive the knowledge of the people's history and their pantheist faith is the intent. Writing about history, people's hearts and freedom - this the story-teller declares to be his heartfelt desire.

The thread of knowledge is spun into a clash of religions, blurring the lines between intuitive and printed knowledge, setting up the acquisition of knowledge as threatening to an intolerant Islamic invading race (when, of course, Islamic cultures have encouraged the arts and sciences in various ways throughout history).

To the invaders, Ansul's multiple gods are demons and the library the mythical mouth of darkness where the final battle between the representatives of (the only) god - the god of fire - and the evil spirits must be fought. Peace is achieved by discussion not war. Compromise seals the deal, not bloodshed. The unwilling heroine feels cheated by the denial of the opportunity to be a real heroine of the people, leading them to the triumphant overthrow of a tyrant. Where other fantasy authors would have revelled in the opportunity to wipe out armies, Le Guin's skill ensures that the narrative struggling to go the way of conventional fantasy is reined in. Always the threat of violence hangs over the text - and a few people do die - but the peace is held.

The deification of the printed word grates a little. The intuitive force of the oracle is reduced to reading from a page - it appears different to different people but even an oracular occurrence has to be printed. The objectification of knowledge as outside the human experience, as needing to be protected from the religious hordes, as dependent on the printed word - these are all problematic oppositions.

The heroine wonders at one point why the songs do not tell how the women managed at home while their husbands and sons hid in the mountains. We wonder too. This side of the story, the novel too glides over. The main action is out there, the heroine is valourised because she holds the masculine attributes of impulsive courage and is almost androgynous. She pats her house help on the head patronisingly for knowing how to 'hem a gusset or gusset a hem, whatever it is,' while she can read. No doubt is left about what the superior knowledge is. Le Guin slips up deliberately here - the part-ancient, part-modern society she describes does not encourage women to read, and this one does.